CJEU in Beevers cheese dispute rules that suppliers must actively protect exclusive distributors

Published on 12th June 2025

Enforceable active sales bans are crucial in exclusive distribution agreements to comply with EU competition law

The Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has clarified that a supplier must actively agree with its other distributors that a territory is exclusively reserved if it wants to appoint exclusively a distributor for that territory.

In its long-awaited Beevers Kaas judgment (Case C-581/23), the CJEU recognised – for the first time – the concept of "parallel imposition" relating to exclusive distribution agreements: if a supplier allocates a territory exclusively to a distributor it must also protect that distributor against active selling by other distributors in the relevant territory.

A mere absence of active sales by other distributors is not enough though: a supplier must reach out to all of its other distributors in order to obtain their acceptance – expressly or tacitly – of the trade restriction. As soon as this can be proven, the appointment of an exclusive distributor can be exempted from competition law.

The court's confirmation has impact on suppliers and distributors alike. On the one hand, businesses using exclusive distributors should evaluate whether they have agreed with all other buyers to respect the exclusivity. Exclusively appointed distributors, on the other hand, should check whether their supplier protects them actively enough.

Cheese distribution dispute

Some Dutch people argue that the best cheese in the Netherlands comes from a polder called "De Beemster". No wonder that cross-border retailer Albert Heijn also desires to sell such cheese in its Belgian stores.

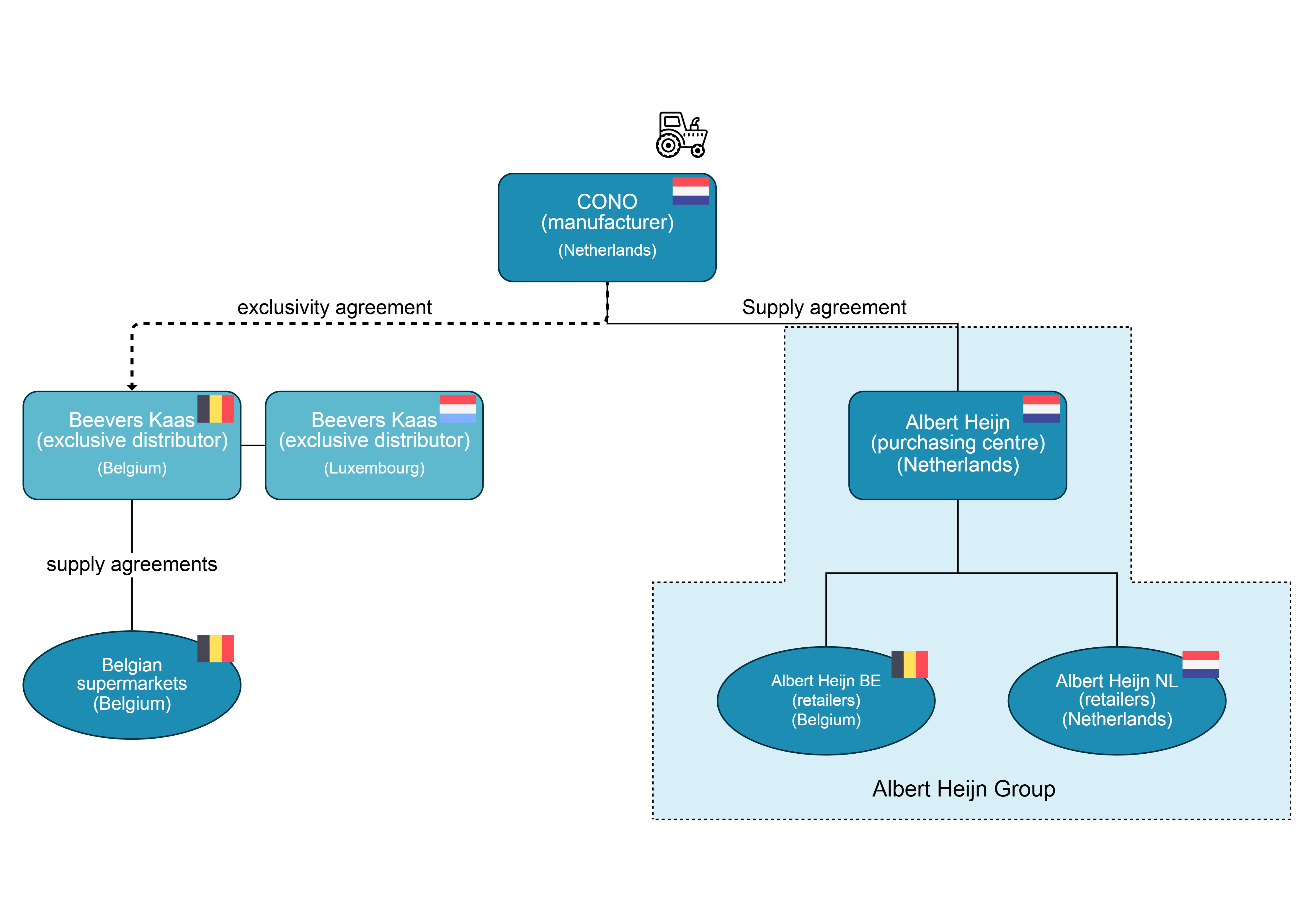

This brought Albert Heijn in conflict with Beevers Kaas, a company appointed by branded "Beemster cheese" manufacturer Cono as its exclusive distributor in Belgium.

Beevers Kaas accused Albert Heijn of breaching the exclusive distribution agreement between itself and Cono, as Albert Heijn has been actively selling Netherlands bought Beemster cheese in its Belgian stores. In its defence, Albert Heijn claimed that the restriction to sell in Belgium amounts to an illegal ban on resale.

Yes, there is such a thing as the 'parallel imposition'

Forbidding to sell actively in a territory is a sales restriction. As such, it could infringe EU competition law. It can nevertheless be allowed if that territory has been reserved for another company. It can even be entirely exempted from competition law if certain criteria are fulfilled, such as if the market shares of the involved companies remain below 30%. This has consistently been laid down in the EU's Vertical Block Exemption Regulation (VBER) that is revised every decade. The VBER was most recently updated in 2022.

What was not laid down (until the 2022 revision) is whether a supplier that agrees to allocate a territory exclusively to a distributor must impose active sales restrictions on its other distributors, so that the exclusive distributor can enjoy its rights. This is known as a "parallel imposition" of active sales restrictions on the other buyers.

The CJEU has now confirmed affirmatively. The obligation on the supplier to protect its exclusive distributors is an integral part of the VBER in order to ensure its effectiveness. And suppliers have to act accordingly. Not satisfying this requirement seems to have as a consequence that the exclusive distribution agreement and the other distribution contracts that did contain an active sales restriction towards the exclusive territory do not benefit from the block exemption and must rely on an individual assessment.

Suppliers and 'parallel imposition'

So how can a supplier satisfy the obligation to impose active sales restrictions on its other distributors to protect its exclusive distributors?

The supplier must reach an agreement – within the definitions of competition law – with each other distributor that it will not actively sell into the exclusive territory (as detailed in point 39 of Beevers Kaas). For this, there must a concurrence of wills. It is not enough if there are no (active) sales from other distributors in the exclusively allocated territory. Absence of other sales cannot only be explained by a tacit acceptation of a sales restriction but also by an autonomous business decision, which is considered unilateral behaviour.

Such agreement is generally possible in various forms. It may come as a distribution contract containing express prohibitions to make active sales in the exclusive territory. But it may also be limited to explicit or tacit conduct of the other distributors that allow the conclusion that these have agreed with an invitation or request from the supplier not to make such active sales (points 42 and 43 of Beevers Kaas).

From what moment then is the exclusive distributor protected?

Another practical issue is the moment as from when the exclusive distributor is protected. Is it for the entire duration of the allocation of the exclusive territory to the distributor? Or is it only for the period in which it can be proven that there was an agreement between the supplier and its other distributors?

The CJEU confirmed that it is the latter: both elements, that is the supplier’s invitation and the distributor’s acceptance thereof, should be demonstrated. In other words, if there is a single distributor that did not agree with the active sales ban, then there is no agreement and, consequently, no protection. Therefore both the exclusive distribution agreement and the active sales restrictions on the distributors that did accept would not benefit from the block exemption. The burden of proof is on the party invoking presence of the active sales ban.

This underscores the dynamic nature of vertical agreements: competition law compliance must be monitored continuously. It places a compliance burden on suppliers and buyers alike to ensure their commercial arrangements remain within legal bounds at all times and not merely at the point of contract formation.

This stringent view of the CJEU, however, seems at odds with the new 2022 guidelines on vertical restraints that allow for a temporary exemption; for example, during renegotiations after modifications to the exclusive distribution network (see the European Commission's 2022 VBER guidelines point 122).

Osborne Clarke comment

Although the analysis of the CJEU is based on the 2010 VBER framework, it remains relevant for the current 2022 VBER framework, as the principles have largely remained the same.

The CJEU's Beevers Kaas judgment underscores the importance of clear and enforceable active sales bans in exclusive distribution agreements. It highlights the need for careful drafting and monitoring of distribution agreements to comply with EU competition law.

First, the parallel imposition requirement means that a supplier must reach an agreement with each distributor before the exclusive distributor is considered protected.

Unless suppliers have a stable distribution network, impose active sales restrictions on each distributor from the start of the distribution relationship (or provide the possibility thereto in their distribution contracts) and have reserved the non-allocated territories for themselves, they must renegotiate every modification regarding exclusivity on their network and receive the approval of every buyer. This may give any incumbent distributor a veto right to the appointment of a new exclusive distributor. An incentive to accept additional active sales restrictions is rather small since this amounts to a limitation of their potential sales market.

Second, according to the CJEU, an exclusive distribution system only benefits from an exemption under the VBER if and insofar as all the other buyers have agreed with the active sales restriction, from the beginning to the end that the benefit is claimed. This goes further than imposing the active sales restriction only when the supplier's other distributors have the intention to actively sell in the exclusive territory, causing them additional administrative burdens. For example, a supplier with an exclusive distributor for Finland will have to impose an active sales restriction on its Spanish distributor in order to benefit from the block exemption, even when the Spanish distributor lacks the means or incentive to sell in Finland.

Measures that businesses can take include:

- Implement an exclusive distribution agreement. Suppliers must have active sales restrictions in place with all their other distributors – this also follows from the definition of "exclusive distribution" as enshrined in article 1(h) VBER 2022.

- Any modification of the EU distribution network, relating to an exclusive distributor, must be reflected in all the distribution agreements.

- Distribution systems including exclusive distributors must be airtight from the beginning to the end (with the possibility of temporary exemptions during negotiations).

For businesses navigating the complexities of competition law and distribution agreements, Osborne Clarke offers expert legal advice. Contact us to ensure your agreements meet EU regulatory requirements and protect exclusive distribution rights.