WHOA | The Dutch equivalent of the US Chapter 11 and UK Scheme of Arrangement is coming

Published on 27th November 2019

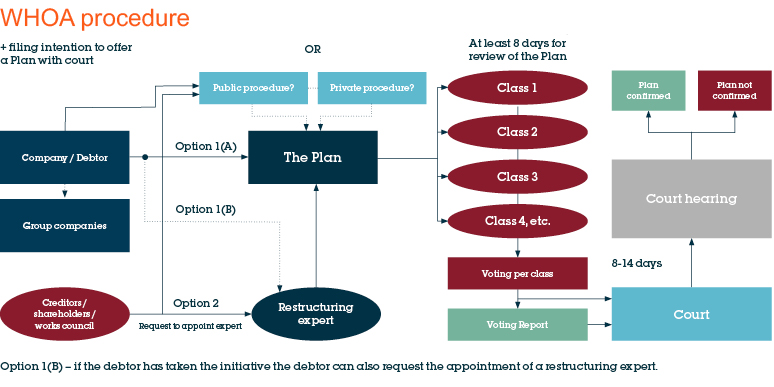

In July 2019, the bill "Wet Homologatie Onderhands Akkoord" – with the rather catchy acronym "WHOA" – was introduced in the Dutch parliament.

The WHOA includes amendments and new sections to the Dutch Bankruptcy Act and will introduce the Dutch equivalent of an UK scheme of arrangement or the US Chapter 11 in the Netherlands. The WHOA is expected to enter into force in 2020. The WHOA is also a first big step in the implementation of the EU Directive 2019/1023 (the Directive), which with some exceptions, Member States are required to implement before 17 June 2021.

The WHOA: in brief

The idea of the WHOA is not new, in fact, in 1835 a bill was proposed that also included the principle that once a majority of creditors accepted the plan of a debtor, the minority should be bound. The rationale is still the same, the rule should prevent an unwilling individual or minority from frustrating the prevention of a bankruptcy. Unfortunately that bill did not make it and neither did a bill that was proposed nearly 60 years later. Even then, the English "Deeds of Arrangements" were referred to as example. In the 90's of the 20th century the idea of the restructuring got some interest again, but it did not lead to any new legislation until a revival in 2012 that started part of the legislative and political process that led to the WHOA.

The WHOA will deliver a toolbox of restructuring possibilities that are currently not available, or available only to a limited extent, in the Netherlands. Our expectation is that only bigger companies will be able to fully utilise this new toolbox due to expected costs in relation to the WHOA. SMEs may, however, also benefit from the WHOA in their position as creditors since bankruptcy of their clients could be avoided.

As with all new legislation, there are some uncertainties on how things will develop in practice and the new WHOA will need to be tested in the field before we can determine how successful it will be. Luckily, the WHOA benefits from years of experience and (foreign) case law with regard to Chapter 11 procedures and Scheme of Arrangements.

The purpose of the WHOA

The purpose of the WHOA is to protect business continuity and the value of viable businesses, by offering companies a legal framework to restructure their debts and/or costs by presenting a restructuring plan (a Plan) to the relevant creditors and therefore preventing moratorium or bankruptcy.

Dutch courts will make available expert panels of specialised judges to deal with WHOA procedures. This is necessary since the procedure develops at a high pace (since time is often of the essence) and the court decision by which the Plan is confirmed or not is final and is not subject to appeal. Once the Plan is confirmed, it is binding on all parties affected by it. This applies to all (secured and unsecured) creditors, including shareholders. Even creditors that have voted against or have not voted for the proposed Plan.

The WHOA cannot affect the rights of employees. Pursuant to the Dutch Works Council Act it may, however, be necessary for management to involve the works council in relation the Plan. For instance, in case the Plan includes the proposal to acquire new financing or disposals of part of the Company: actions that would normally require advice from the works council. Getting the works council aligned may be challenging given the short time frame in which the Plan needs to be prepared.

Who can apply for the WHOA procedure?

A debtor that is in a position where it is reasonably likely that it will not be able to continue to pay its debts (the Insolvency Test), may offer a Plan to (part of) its creditors and shareholders. If the debtor is a legal entity, its management does not need approval from its shareholders to start a WHOA procedure. Once the debtor starts to prepare the Plan, it will need to register a declaration about its intention with the court. Before the court has made its first decision in respect of the procedure, the debtor must indicate whether or not it will opt for the private or public procedure (see more on this below).

The initiative for restructuring may also come from a creditor, shareholder, works council or other employee representative. One or more of these parties may ask the court to appoint a restructuring expert who will prepare a Plan. The requesting part(y)(ies) also need to indicate whether the procedure should be public or private. So the choice of a public or private procedure needs to be made at an earlier stage if the initiative is not with the debtor. The court does need to give the debtor the opportunity to express its views the choice between a public or private procedure.

A request made by parties other than the debtor will be granted if the Insolvency Test is met (the court can appoint experts to verify this), unless this would not be deemed to be in the best interest of the joint creditors.

Critics of the WHOA state that, although the intention of the WHOA is a noble one, it is very likely that the class of companies that can effectively restructure using the WHOA is probably limited to large corporations that have the budgets needed to hire advisors for the company as well as the restructuring expert that is likely to be appointed to oversee the process. This means that SMEs (Small-to-Medium Enterprises, which comprise approximately 99% of the companies in the EU – according to the Directive) that usually already have less leverage with their creditors, may not be able to enjoy the benefits of the expensive WHOA procedure. They may, however, still indirectly benefit from the WHO in their role as creditors/suppliers of bigger companies that successfully restructure using the WHOA.

As set out in the recitals of the Directive, the Directive also recognises that SMEs are more likely to be liquidated than to be restructured due to the costs of restructuring procedures. Although the Directive includes the obligation for Member States to make available online restructuring checklists and guidance in an attempt to decrease restructuring costs, we expect that, although templates and guides are a nice starting point, most of the advisory fees will be incurred in time spent in actually checking the boxes of those checklists, drafting documentation, advising management, preparing the strategy, process management, or negotiations, amongst other things.

The WHOA is not available to debtors that are insurers or banks since those institutions have their own dedicated "restructuring" proceedings.

Public or private WHOA procedures

The public procedure

The public procedure is only available to debtors having their "centre of main interests" (COMI) (as that term is used in article 3(1) of EU Regulation 2015/848 of 20 May 2015 on insolvency proceedings (recast) (the EU Insolvency Regulation)) in the Netherlands.

The public WHOA procedure will be registered with the Dutch trade register and in the insolvency register. The public WHOA procedure will also be subject to the EU Insolvency Regulation and will therefore have the advantage that it will be automatically recognised in all Member States (with the exception of Denmark).

The private procedure

The private procedure is available for debtors: (i) having their COMI in the Netherlands, or (ii) for which the Dutch courts have jurisdiction on the basis of section 3 of the Dutch Code on Civil Procedure (DCCP), meaning that the "requesting party" of a WHOA procedure would either: (i) need to have its residence or seat in the Netherlands, or (ii) have a sufficient connection with the Netherlands.

Interestingly enough, section 3 of the DCCP only speaks about the "requesting party". This could mean that if someone other than the debtor, let's say a creditor located in the Netherlands, requests the private procedure, neither the COMI nor the corporate seat of the debtor needs to be in Netherlands and that the debtor does not need to have any connection with the Netherlands. If intended, this would broaden the reach if this procedure significantly for foreign companies. This is a strategy that also worked for the popularity of the US Chapter 11 procedure (where having a US bank account was often sufficient to create nexus with the US court) and the UK Scheme of Arrangement (for which having creditors in the UK and/or changing the governing law of a loan agreement to English law has in some instances been deemed sufficient).

The advantage of the private procedure (other than not having to have COMI in the Netherlands) is that all requests in relation to the procedure will be dealt with by the court behind closed doors (non-public). This allows the debtor to offer a Plan to a select few key creditors and avoid negative publicity and potential adverse consequences thereof.

A disadvantage is that the private procedure is not subject to the EU Insolvency Regulation and recognition in other jurisdictions is subject to the applicable recognition principles of the relevant jurisdiction. We expect that the so-called "recognition opinions" known from cross-border UK Schemes of Arrangement may be introduced in this respect.

View a full size version of this diagram

The Plan and the process

The contents of the Plan

Under the WHOA, the Plan can be offered to some or all of the creditors and shareholders. The Plan can alter rights against the debtor of any creditor or shareholder class. And under certain conditions also rights against the group companies of the debtor, enabling the restructuring of the whole group.

The WHOA offers quite some flexibility with regard to the contents of the Plan. The Plan could, for instance, include any of the following proposals or a combination thereof:

(a) a write off of claims (a 'haircut'); and/or

(b) a debt for equity swap (which may include changes to articles of association or shareholder agreements next to issuance of new shares); and/or

(c) a suspension of payments.

The WHOA also offers the possibility to terminate contracts with three months' notice if a counterparty does not accept the proposed changes to the contract. Such changes could include a price adjustment of a supply contract, a reduction of the amount of sq. meter in a lease agreement, or changes to a building contract that is lossmaking. The claims for damages in case of a termination can be included in the Plan as well.

There are several useful supporting provisions in the WHOA that also increase chances of success, such as:

(a) Provisions rendering contractual rights to terminate contracts upon insolvency unenforceable.

(b) The protection of emergency funding against annulment actions by a bankruptcy if the Plan is not successful.

(c) The option to request that a court promulgate a cooling off period of a maximum of four months. This prevents creditors from enforcing their (security) rights, to attach goods and assets. It will also suspend any pending requests for moratorium or bankruptcy proceedings.

(d) The ability for the Plan to include sureties, jointly liable parties and co-debtors. A creditor that would lose part of its claim due to a confirmed Plan can still claim 100% of its claim against, for instance, the guarantor. The guarantor can in that case not take recourse against the debtor for the 100%. The surety instead gets the same rights the original creditor would have had under the Plan.

But as with all new legislation, there are also some things not entirely clear and the restructuring process will always remain challenging.

Classes

It is up to the debtor to organise the shareholders and creditors into classes. There is flexibility in this respect, provided that shareholders and creditors can only be included in a class if, before the Plan, they have comparable rights vis-à-vis the debtor.

According to the WHOA, creditors having different ranking on the basis of Dutch law (for example, secured creditors, unsecured creditors, subordinated creditors or shareholders) cannot be put in the same class. Taking this minimum requirement into account, there are still quite some variations possible. Shareholders could be divided in several classes, based, for instance, on priority rights or on the basis of added value to the company continuity. The same goes for unsecured creditors that may rank parri passu in bankruptcy, but that could be divided in several classes. Only creditors or shareholders whose rights are affected need to be put in classes.

It will probably be possible that certain parties take part in different classes with different claims: for instance, a shareholder that is also a creditor under a shareholder loan or is also a key supplier of the company.

Voting

Classes will become relevant once the relevant creditors and stakeholders need to vote for or against the Plan. If creditors/shareholders representing at least two thirds of the capital/claims of a class vote in favour of the Plan, the Plan is adopted by that class.

Voting in shareholder classes takes place without taking into account the rules of corporate law regarding voting and other voting arrangements. This means that shareholders without voting rights can still vote and that economic beneficiaries (for instance having rights of usufruct (vruchtgebruik) or holders of depositary receipts of shares (certificaathouders)) can vote as well. This can be achieved either by giving the legal owner the obligation to vote in line with the wishes of the beneficiary or by granting the voting rights directly to the beneficiary instead of the legal owner. What method is appropriate depends on the relevant circumstances.

Within seven days after the voting has taken place, the debtor or expert needs to prepare a report and file this report with the court.

Court confirmation of the Plan

Once all classes have voted and at least one class of creditors/shareholders has voted in favour of the Plan, the court can be requested to confirm the Plan. If the debtor is an SME, the debtor also needs to approve that request (if made by the creditors). If only one class voted in favour of the Plan, this class needs to consist of "in the money creditors" (creditors that would get cash consideration in case of bankruptcy).

The court must deny the confirmation request if certain minimum conditions are not met. There are general conditions that the court will test ex officio. Examples are the Insolvency Test mentioned earlier, where the performance of the Plan is not sufficiently safeguarded, or where the debtor wishes to raise new financing as part of the Plan and this is not deemed to be in the best interest of the creditors jointly.

There are also conditions that need to be tested only following the request of parties that voted against. Upon request of one or more creditors/shareholders with voting rights, which voted against or which were unjustly not admitted to the voting rights, the court can refuse the Plan if there are reasons to believe that such creditors/shareholders are worse off with the Plan than they would be in a bankruptcy. This is referred to as the "best interest test". Given the position of shareholders in a bankruptcy, this does not have much importance for shareholders, however.

If not all classes have voted in favour of the Plan, upon request of one or more shareholders/creditors that are part of the class that voted against the Plan, the court must deny the Plan, in short:

(a) if the Plan deviates from the statutory ranking of the shareholders/creditors involved, unless:

(i) there are reasonable grounds for this; and

(ii) if the interests of the class that voted against would be adversely affected; or

(b) if the parties of the class that voted against would, on the basis of the Plan, not have the option to receive a cash amount that would at least be equal to the amount of cash to be received in case of a bankruptcy.

The ground mentioned under (a) above is inspired by the US "Absolute Priority Rule". For example, key shareholders (founders, directors or strategic partners) that get a better position in the Plan than they would normally get as shareholder. There are circumstances where this is justified because these key shareholders are necessary to make the restructuring a success (whether or not in combination with provision of new capital).

The court will organise a court hearing within 8 to 14 days after the voting report has been registered and the request for confirmation of the Plan has been made. Since the voting report and the request can be filed on separate dates, we assume the later date will be used. It is of course in favour of the debtor to file the voting report as soon as possible since creditors/shareholders are allowed to file their objections against the Plan up until the day before the hearing.

Conclusion

In the 19th through to the 21st century, a few attempts have been made to introduce legislation in the Netherlands that would allow a debtor to escape its insolvency if it could reach an agreement with the majority of its creditors. We have good hopes that nearly 185 years after the first proposal was made, the WHOA is now close to being adopted.

As noted, the WHOA will likely be most useful for bigger companies. But those companies are often the clients and customers of smaller companies and therefore this will also help smaller companies in a way. The WHOA is not perfect, but we think that the WHOA-toolbox indeed includes the most important tools for a successful restructuring. It is up to the stakeholders, their advisors and to the judges to make creative use of the tools the WHOA will offer.