VC Focus | Guide for structuring VC funds in the Netherlands

Published on 24th March 2023

What are the most commonly used Dutch fund vehicles, how are they treated for tax and what is the Dutch regulatory regime for AIFMs?

The Netherlands is becoming an increasingly popular jurisdiction among venture capital (VC) managers for the purpose of structuring their VC funds. There are multiple reasons for VC fund managers to choose the Netherlands:

- It is considered to be one of the leading start-up ecosystems for VC in Europe and Amsterdam is ranked the #1 startup ecosystem in the EU by Startup Genome in 2022.

- The costs of structuring a fund in the Netherlands are relatively low compared to other EU jurisdictions (especially Luxembourg).

- The Netherlands is logistically an easy place to travel to and from.

- Dutch-based VC funds that are managed by a licensed Dutch fund manager or with an EuVECA (European Venture Capital) label can be offered in other EU jurisdictions by using a passport.

- VC managers can make use of the Dutch Seed Capital Scheme (DSCS) if their funds invest in technological or creative start-up companies. Closed-end VC funds can obtain an interest free loan under this DSCS from the Dutch government up to an amount of 50% of the total commitments within a VC fund.

This guide for (potential) VC managers outlines the structuring of VC funds in the Netherlands, covering the most commonly used Dutch fund vehicles, the Dutch tax treatment of those vehicles and the Dutch regulatory regime for alternative investment fund managers (AIFMs).

Fund vehicles

VC funds in the Netherlands are typically structured in the form of a co-op (coöperatie), Dutch limited partnership (commanditaire vennootschap) (CV), fund for joint account (fonds voor gemene rekening) (FGR) or a private liability company (besloten vennootschap) (BV).

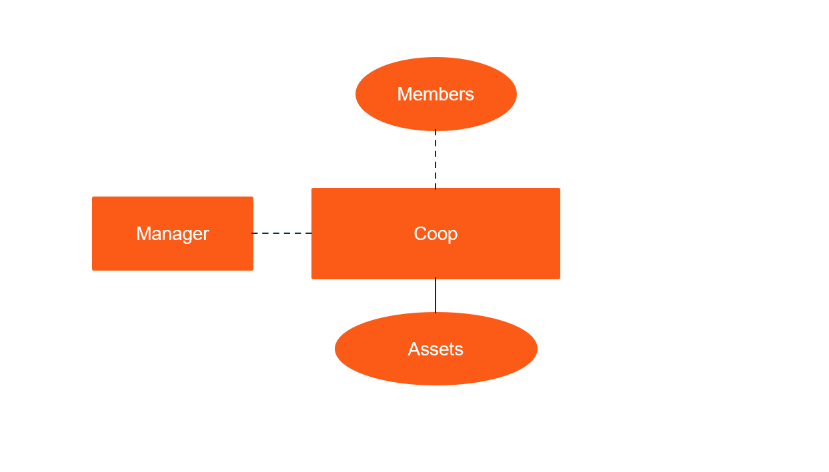

- Co-op

-

The co-op allows for a flexible fund structuring and they can, subject to certain conditions, be structured as fiscally neutral tax opaque funds for corporate and dividend tax purposes. Co-ops are eligible to benefit from the DSCS.

The co-op is a special form of association. They do not have a capital that is divided into shares, but the investors participate in it as members with pro-rata membership interests in it. The co-op is primarily governed by its articles of association, but in practice a membership agreement further arranges the relationship between the co-op, the members and the co-op's manager.

Management

The manager carries out the day-to-day management of the co-op pursuant to its articles of association. The manager is often structured as a BV (besloten vennootschap – private liability company).

The manager is in practice often responsible for both the management of the co-op (as statutory manager of the BV) and the fund (as AIFM). The manager can delegate its fund management tasks to third parties subject to certain limitations set out in the AIFMD (Directive 2011/61/EU) and the AIFMR (Commission Delegated Regulation EU 231/2013). The manager's liability is usually limited in the membership agreement.

Members

The rights of the members within a co-op follow from its articles of association and the membership agreement. Member's rights typically include voting rights at the annual meetings of the co-op and the limitation of their liability for an amount up until their total investments (although this limitation is subject to certain exceptions).

Formalities

Co-ops are established by notarial deed executed in front of a Dutch civil law notary. Co-ops must register with the Dutch Chamber of Commerce (Kamer van Koophandel) by registering their articles of association. The articles of association of a co-op are publicly available, whereas the membership agreements are kept private.

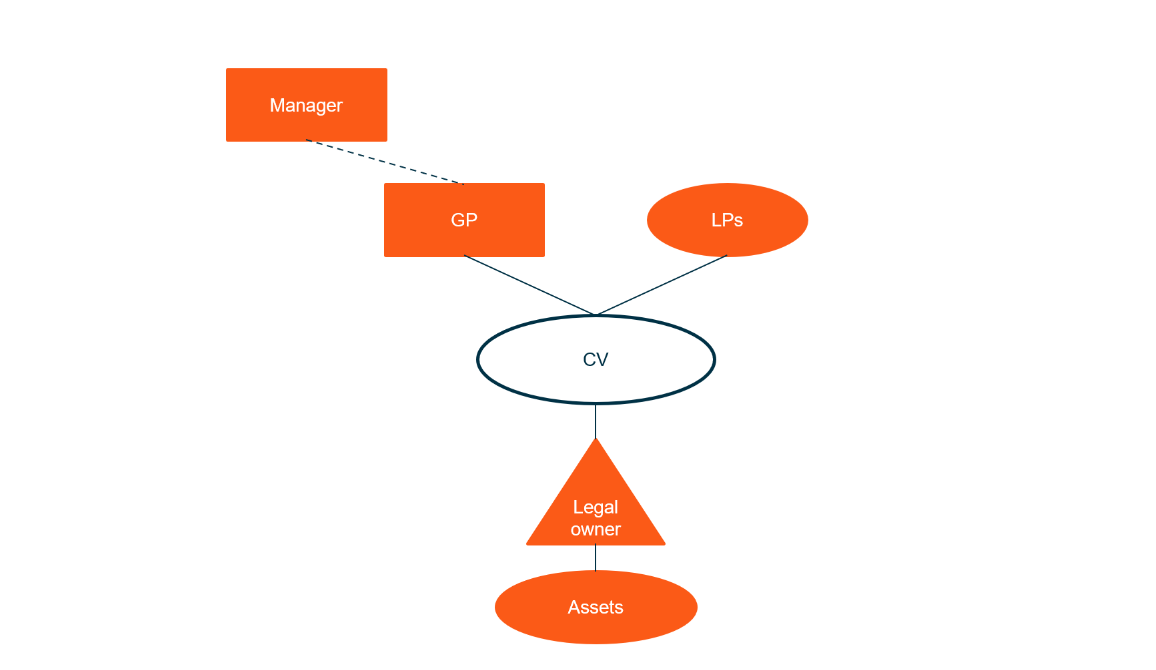

- CV (Dutch limited partnership)

-

The CV is often used for a fund structure for international investors. It is similar to US and English limited partnerships and is well known to both Dutch and international investors. It allows for a very flexible structuring and is typically structured as tax transparent. CVs are eligible under the DSCS.

The CV is a Dutch limited partnership established by an agreement (a limited partnership agreement or LPA) between a general partner (GP), the investors and the legal owner (as defined below).

Management

The GP has the responsibility of carrying out the day-to-day management of the CV. The GP is jointly and severally liable for the debts of the CV towards third parties.

A GP is usually established in the form of a Dutch private limited company (besloten vennootschap) (BV) that is set up for the sole purpose of acting as the GP.

The GP of a fund that is structured as a CV is responsible for appointing an alternative investment fund manager, which is usually done by means of a management agreement. The manager is usually structured as a BV and is separated from the GP for regulatory and/or liability reasons.

Tasks of the manager include the fund's portfolio management, risk management, administration, marketing and other tasks set out in Annex 1 of the AIFMD. These tasks can be delegated to third parties subject to certain limitations set out in the AIFMD (Directive 2011/61/EU) and the AIFMR (Commission Delegated Regulation EU 231/2013).

Investors

The investors within a CV qualify as limited partners (LPs). The LPs are only liable up to the amount of their contributions to the CV, as long as they do not act on behalf of or for the benefit of the CV towards third parties. This follows directly from the Dutch Commercial Code.

Formalities

CVs do not have legal personality and cannot hold their own assets. The Dutch Financial Supervision Act (DFSA) prescribes that the ownership of the assets in a fund without legal personality must be held in a separate entity with the sole purpose of acting as title holder for the assets and liabilities of the fund (a legal owner). It is usually structured as a Dutch foundation (stichting), which is a legal entity with legal personality that exists for a specific purpose and is in practice managed by the manager, GP or other affiliated persons.

CVs that are managed under the sub-threshold regime (discussed below) do not have to appoint a separate legal owner.

A CV is established by the execution of the LPA. This can be done through a notarial deed, but is generally done by way of a private deed. CVs have to be registered with the Dutch Chamber of Commerce, although the legal partnership agreement does not have to be registered and can be kept private.

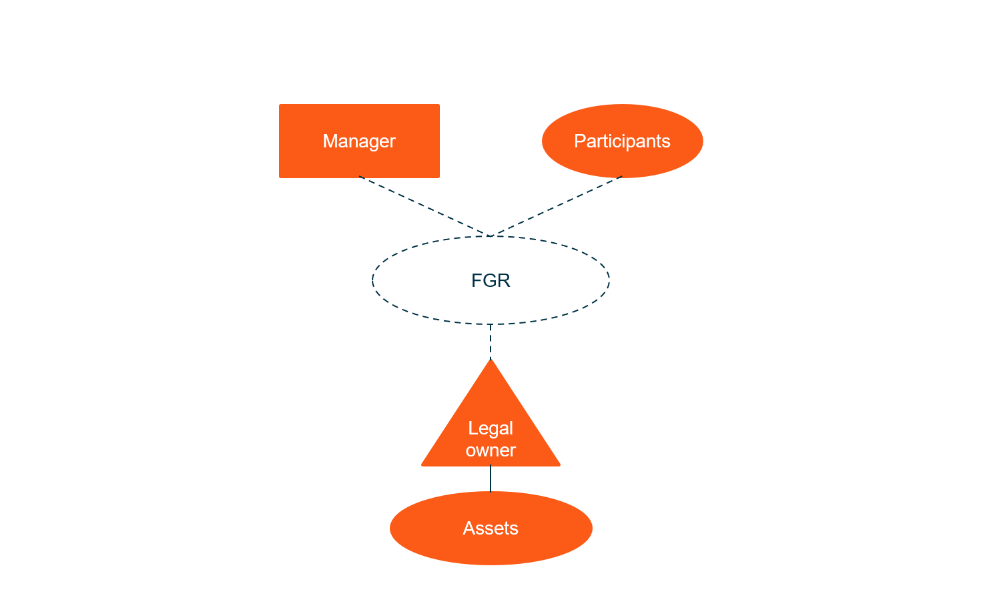

- FGR (fund for joint account)

-

The FGR is well known within the Dutch investment funds market and is known as the most flexible fund structure in the Netherlands. The FGR is typically structured as tax transparent. FGRs are not, in principle, eligible for funding under the DSCS.

An FGR is a contractual arrangement sui generis (often referred to as the terms and conditions) between the manager, the individual investors and the legal owner.

Management

The AIFM of the FGR is usually established in the form of a Dutch private limited company (besloten vennootschap) (BV).

The FGR's AIFM is directly responsible for carrying out the duties that are set out in the terms and conditions, including the fund's portfolio management, risk management, administration and marketing (these tasks can be delegated to third parties subject to certain limitations set out in the AIFMD (Directive 2011/61/EU) and the AIFMR (Commission Delegated Regulation EU 231/2013). The manager's liability is usually limited in the terms and conditions.

Investors

The investors in an FGR are usually referred to as participants. The participants in an FGR are in principle liable up to the amount of their contributions to the FGR, as typically follows from the terms and conditions.

Formalities

The FGR is not a legal entity, nor has legal personality, and cannot hold its own assets. The DFSA prescribes that the assets of a fund that is structured as an FGR must be held in a legal owner. A legal owner is usually structured as a Dutch foundation (stichting) and is managed by the manager or other affiliated persons. FGRs that are managed under the sub-threshold regime (as discussed below) do not have to appoint a separate legal owner; assets can in that case be held by the manager directly.

An FGR is established by the execution of the terms and conditions. This can be done through a notarial deed, but is generally done by way of a private deed. Registration of an FGR with the Dutch Chamber of Commerce is not required.

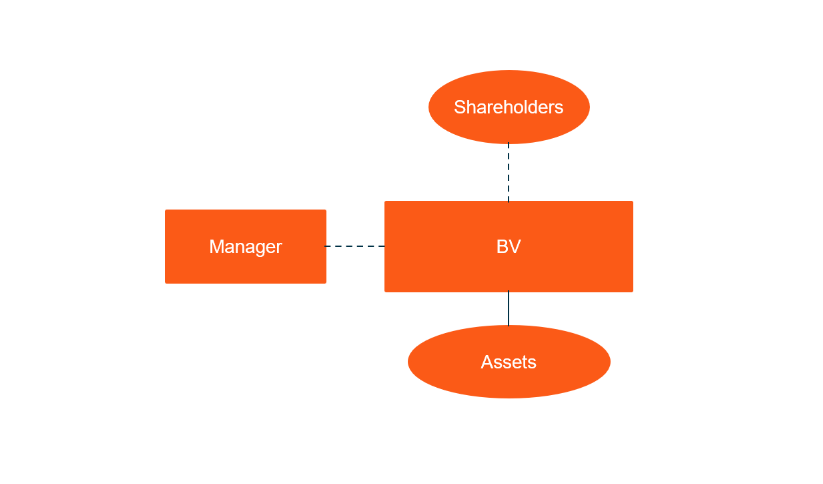

- BV (private liability company)

-

BVs are Dutch private liability companies that are used as fund vehicles, which under strict conditions may be subject to Dutch corporate income tax at a rate of 0% (as explained below). BVs have legal personality but nonetheless are quite flexible fund structures. BVs are eligible under the DSCS.

The capital of BVs is divided into shares. BVs are governed by the Dutch Commercial Code (Burgerlijk Wetboek) (the DCC) and the BV's articles of association.

Management

The day-to-day management of a BV is conducted by the statutory directors of the BV, as prescribed by the DCC. The statutory director of a fund structured as a BV is usually the manager of the fund.

The manager is in that case responsible for the day-to-day management of the BV as well as for the management of the fund (although the latter responsibilities can be delegated to third parties subject to certain limitations set out in the AIFMD (Directive 2011/61/EU) and the AIFMR (Commission Delegated Regulation EU 231/2013)

The appointment of the manager as statutory manager of the BV takes place in accordance with the BV's articles of association and is usually done by the means of a management agreement between the BV and the manager. The liability of the manager is limited in accordance with the DCC, meaning that the manager is in principle not liable for the BV's debts, though certain exceptions can apply.

Investors

The investors in a BV qualify as shareholders and together hold the capital in the BV.

The rights of the shareholders, such as rights with respect to dividends, voting powers and the right to transfer shares mainly follow from the BV's articles of association but can optionally be regulated further in a shareholders' agreement. The shareholders are in principle not liable for losses of the BV, although certain (limited) exceptions can apply.

Formalities

The BV has legal personality. As such, the assets of the BV can be held directly by the BV and do not have to be held by a separate legal owner.

A BV is established by a notarial deed, executed in front of a Dutch civil law notary. BVs must register with the Dutch Chamber of Commerce by registering the articles of association. The articles of association of a BV are publicly available. Shareholders' agreements that further arrange for the relationship with the shareholders and the manager can however be kept private.

Tax treatment

Funds can be structured in opaque or transparent form. Tax opaque funds are subject to Dutch corporate income tax and withholding taxes, whereas tax transparent funds are not. The taxation in tax transparent funds finds place at the level of the investors as the income, assets and liabilities in transparent funds are attributed directly to the investors in tax transparent funds.

- Tax transparent funds

-

Funds structured in the form of CVs or FGRs are eligible to be structured as tax transparent funds. Tax transparent funds are required to be "closed" for tax purposes. There are, insofar relevant, two ways in which a CV or FGR can be structured as "closed" for tax purposes:

- Investors in a CV or FGR can, in short, only transfer their participations in a CV or FGR after obtaining prior written approval of the manager and all other participants in the CV or FGR; or

- In the case of an FGR, the participations of an FGR can (insofar relevant) only be transferred to the FGR itself for redemption out of its assets.

The regime for tax transparent funds does not impose any restrictions on the number or type of shareholders, the type of investments or the distribution of proceeds.

However, the Dutch legislator is currently preparing changes to the tax regime for CVs and FGRs:

- CVs will under this new regime, as a general rule, be treated as transparent for Dutch tax purposes by default. This proposed amendment brings the tax treatment of CVs more in line with the international tax treatment of limited partnerships.

- It is further proposed that only FGRs that qualify as AIFs under the DFSA with publicly traded participations qualify as opaque for Dutch tax purposes (as discussed in more detail in our FS insight).

- Tax opaque

-

Tax opaque funds are "open" for tax purposes and are in principle subject to Dutch corporate income and dividend withholding tax. However, co-ops can be structured in a way that they are exempt from Dutch dividend tax and certain open funds can opt for the status of an exempt investment institution (vrijgestelde beleggingsinstelling) (VBI) or fiscal investment institution (fiscale beleggingsinstelling) (FBI) which are both exempt from Dutch corporate tax income.

Co-op

Co-ops are subject to corporate income tax on worldwide income. However, the corporate income tax exemption and withholding tax exemption can apply.

At fund level, investments made by VC funds are typically eligible for this participation exemption, as a result of which co-ops should not be subject to Dutch corporate income tax on dividends and capital gains derived in connection with qualifying investments.

At investor level:

- Dutch corporate investors in co-ops are often exempt from Dutch corporate income tax on dividends and capital gains derived in connection with their investment in a co-op under the participation exemption.

- Non-Dutch corporate investors can only be subject to Dutch corporate income tax on income/gains derived from their investment in a co-op if, in short, an abusive situation applies, which could be the case if the main purpose of the structure the investor and co-op form part of is to avoid corporate income tax.

Distributions made to co-op are not subject to Dutch dividend withholding tax if it is structured as "active" for tax purposes. Co-ops with only Dutch corporate investors as members do not have to be structured as active co-ops because these investors can directly benefit from Dutch domestic participation and withholding exemptions (or refunds).

The co-op tax regime is, in practice, often used for VC funds with mainly Dutch (corporate) investors, as these investors are typically exempt from corporate and dividend withholding tax under the tax withholding exemption and participation exemption. The tax regime for co-ops does not impose any restrictions on the minimum number of investors within it or on the distribution of proceeds by it.

FBI

The FBI is in practice often used by VC fund managers. It is subject to Dutch corporate income tax at a rate of 0% and, as they are considered a tax resident of the Netherlands, they generally qualify as residents under the double tax treaties concluded by the Netherlands.

FGRs and BVs can both be structured as FBIs, whereas CVs and co-ops are not eligible to be structured as FBIs.

BVs or FGRs that are structured as an FBI have to, among other things, meet the following cumulative requirements in order to qualify:

- the objective and actual operation exclusively consists of investing;

- the use of leverage is, insofar relevant, maximum 20% of the tax book value of the assets;

- proceeds have to be distributed to the shareholders within eight months after the financial year; and

- the following shareholders' restrictions are applicable: (i) if the fund is managed by a full scope licensed AIFM or the shares of the fund are traded on a regulated market, a maximum of 25% of the participations or the shares of the fund can be held by a single natural person; or (ii) if the fund is not managed by a full scope licensed AIFM and the shares of the fund are not traded on a regulated market, a maximum of 5% of the participations or the shares of the fund can directly or indirectly be held by a single natural person.

Profit distributions made by the FBI are generally subject to 15% Dutch dividend withholding tax, unless an exemption applies.

VBI

A VBI is, unlike the FBI, completely exempt from both Dutch corporate income and dividend withholding tax. VBIs can be structured as FGR, whereas CVs, BVs and co-ops cannot qualify as a VBI.

An FGR that is structured as VBI needs to meet the following cumulative requirements:

- it invests in financial instruments (such as shares) with the aim of risk diversification; and

- the participations of an FGR are, upon the request of the participants, purchasable or redeemable out of the FGR's assets.

The VBI-regime does not impose other restrictions to funds, such as minimum distribution requirements or restrictions to the types of shareholders.

The Dutch legislator is currently considering imposing additional eligibility criteria for VBIs in order to exclude so-called family VBIs from the VBI-regime. The legislator considers to only open the VBI-regime for VBIs that are under full-scope AFM supervision (as discussed below). The amendments to the VBI-regime are expected to be formalised in September 2023.

Regulatory regime

Under the DFSA, VC managers can be required to obtain a full scope licence in order to manage alternative investment funds (AIFs). Alternatively, a third party AIFM can be used for managing AIFs or VC managers can rely on an exemption from the licence obligation, of which the sub-threshold regime (possibly combined with a EuVECA label) is in practice often used.

- Full scope licence

-

Managers can apply for a full scope licence to manage one or more AIFs with the Dutch Authority for the Financial Markets (AFM). The licence requirements for managing AIFs consist, among others, of requirements regarding governance and control, the suitability and integrity of the daily policymakers of the AIFM, conflicts of interest, financial solidity, risk management and anti-money laundering. The AFM further requires substance, which means that a certain amount of the AIFM's staff must work in the Netherlands.

Licensed AIFMs are further required to register all AIFs under their management with the AFM. A registration of an AIF with the AFM requires, among other things, fund documents (such as an LPA/terms and conditions and an information memorandum/private placement memorandum) that meet the disclosure requirements, including the disclosure requirements following from the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). A depositary must further be appointed for each AIF under a licensed AIFM's management.

Licensed AIFMs can upon the registration of an AIF market their AIFs in other EU jurisdictions under a cross-border passport. Licensed AIFMs can alternatively rely on reverse solicitation.

- Third party AIFMs

-

Certain EU jurisdictions allow parties to initiate a fund through a licensed AIFM (often referred to as the third party AIFM). The third party AIFM is in this structure typically responsible for the risk management of the fund, while the initiating party (often referred to as the investment advisor) is responsible for (factually) conducting the portfolio management of the fund.

The AFM allows the use of third party AIFMs. However, the AFM does in practice require that the third party AIFM and investment advisor comply with the portfolio outsourcing requirements that follow from the AIFMD (Directive 2011/61/EU) and the AIFMR (Commission Delegated Regulation EU 231/2013).

- Sub-threshold regime

-

The sub-threshold exemption is available to managers whose assets under management – briefly put – do at the aggregated level not exceed €500 million, or in case of leveraged or open-end funds, €100 million. In addition, the manager must offer the managed AIFs to (i) exclusively professional investors, (ii) less than 150 individuals, (iii) with a minimum equivalent value of €100,000 or (iv) with a minimum nominal value of €100,000.

Sub-threshold managers must register with the AFM prior to commencing the management of an AIF. The processing time for such a registration is considered to be two weeks.

Sub-threshold AIFMs are exempt from the prudential and conduct of business requirements that follow from the DFSA. This includes an exemption from the requirement to appoint a separate legal owner for funds without legal personality (such as the CV and FGR).

Sub-threshold AIFMs must however, among other things, annually report their financial data to the AFM, comply with the Dutch anti-money laundering provisions and comply with the disclosure obligations following from SFDR. Sub-threshold AIFMs cannot in principle distribute their funds cross-border within the EU using a passport, but can: opt for a EuVECA label (as discussed below), rely on reverse solicitation or distribute their AIFs under local National Private Placement Regime (NPPR) in a number of EU jurisdictions.

- EuVECA

-

Sub-threshold managers that manage VC funds can opt for a EuVECA label, which has increased in popularity over the last few years. This EuVECA label allows VC sub-threshold managers to passport their funds cross-border within the EU without obtaining a full-scope licence. The requirements that apply to EuVECA funds and their managers include the following:

- EuVECA funds are required to invest a minimum of 70% of its capital in SMEs with a maximum of 499 employees;

- EuVECA funds may only be offered to (i) professional investors; or (ii) retail investors that commit to investing a minimum of €100,000 and state in writing that they are aware of the risks associated with their investments;

- the manager of the EUVECA fund needs to meet a number of criteria in respect of, amongst others, conduct of business, outsourcing, capital requirements, valuation of assets, reporting and disclosures; and

- the daily and co-policymakers of the EUVECA fund need to be assessed as fit and proper for the performance of their tasks by the AFM.

Osborne Clarke comment

VC funds in the Netherlands are typically structured as a co-op, CV, FGR or BV.

The co-op is a special form of association with investors as its members and has as its main advantage that can be structured as a fiscally neutral tax opaque fund for corporate and dividend tax purposes.

The CV and FGR look alike, are established by agreement and both allow for a very flexible fund structuring. In practice, the CV is most used internationally, as it is more well-known by non-Dutch investors. The FGR enjoys a bit more flexibility in its tax treatment, as it can be structured as tax transparent, VBI and FBI.

BVs have legal personality and do not require a separate legal owner. BVs can be structured as FBI which is subject to Dutch corporate income tax at a rate of 0%.

AIFMs can manage their AIFs in the Netherlands as full scope AIFMs with a licence or as sub-threshold AIFMs (with the possibility to opt for a EuVECA label for cross-border marketing). VC funds can alternatively make use of a third party AIFM.

If you would like to discuss this further, please get in touch with your usual Osborne Clarke contact, or one of our experts below.